Include Me Out

A call for ideas, opinions, and an invitation to share with us the projects of your dreams. (What we talk about when we talk about access, 2025 edition.)

Here’s the official video for British post-punk band IDLES song “Mr. Motivator”. During deep lockdown, we had been asked by the band’s promotional representatives to send in a video clip with a very specific aesthetic. (At that time, IDLES had a particularly close fan/band base, and it was clear someone had seen that Tuck and I Made Stuff and Dressed Up.)

Out of the thousands of clips requested, we made it into the 200+ that appear in the video. It was a real treat.

Can you find us?

“Mr. Motivator” was one of the very first music videos I saw influenced by pandemic conditions, and created by bringing together hundreds of people all over the world through digital participation, because there was no choice but to do so.

Also, one of my then-favorite parade groups to follow, Handmade Parade in Hebden Bridge (England), went virtual for their parade in 2020 — and, one of the percussionists in the big ensemble at the end is, indeed, Béla. Recorded in lockdown in Philly, mixed over yonder. (Go Burnley).

After lockdown, our first reunion with our friend and collaborator Zach Inkeles was this podcast.

https://folkfuturism.org/2022/10/14/art-reach-cultural-accessibility-conference-2022-with-art-reach/

The audio from the talk is available here. It makes me miss Zach so much. I did hear from him over the holidays, and he is now forging ahead with the ideas we shared here, in his new home in Denver.

There was a time, when we forged Folkfuturism as a collective, that our experience came from a place of leadership. If we were going to be involved, it was expected (by others) that we would teach. We saw this as our contribution to the community — not the arts community, but our community.

If there was a slot open for speakers, I was always ready to speak — in front of an audience, on the radio. And when we thought about the work we made, we always prioritized finding people who wanted to do similar work, and had found barriers to doing so before, and we worked to remove those barriers by partnering with other events and organizations.

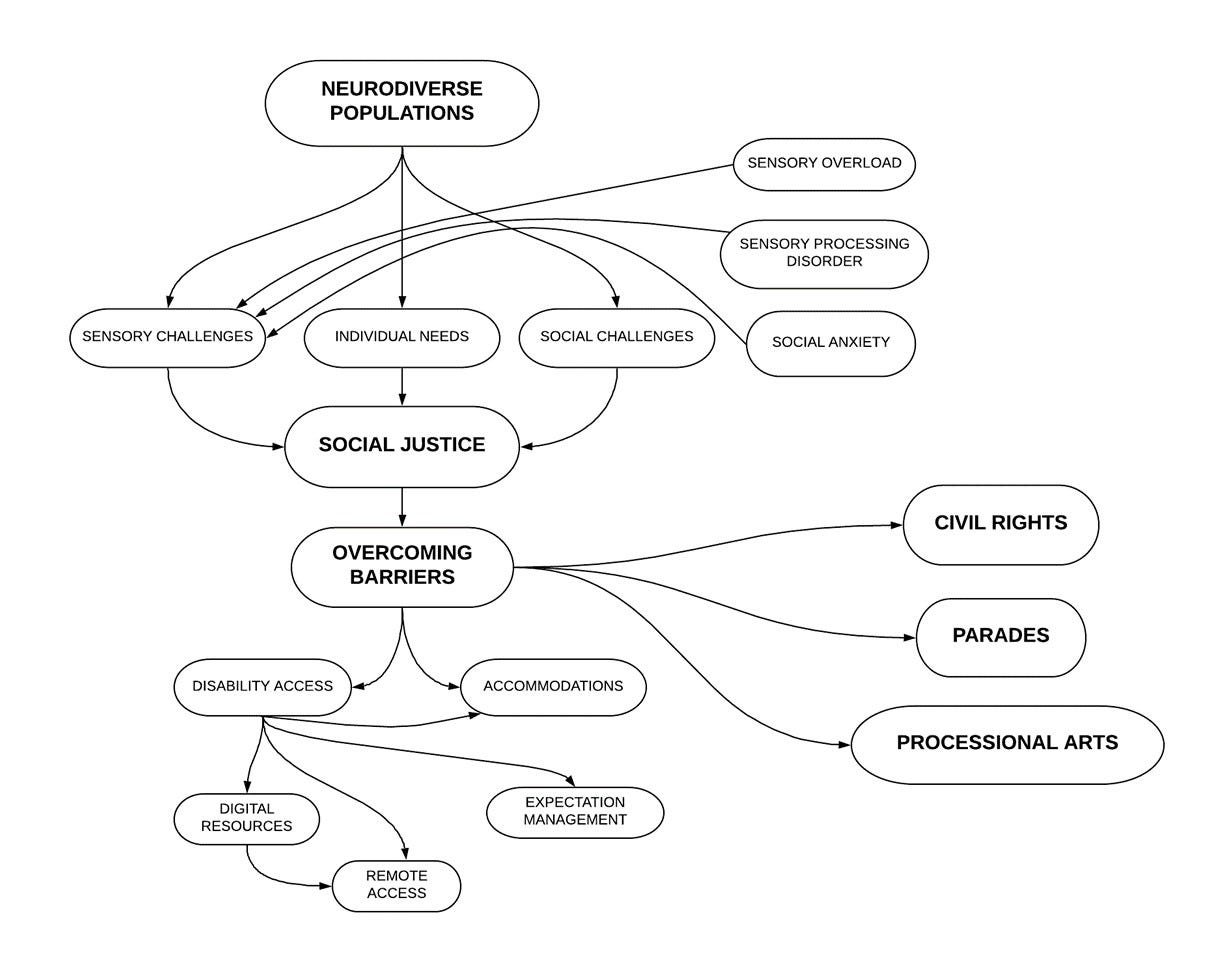

Our early projections for what Tucker and I both wanted to do, and felt served the communities we wanted to represent, looked like this:

concept maps by Tucker J. Collins. DO NOT COPY OR SHARE. Contact with questions at folkfuturism@gmail.com.

Processional arts are culturally and artistically significant and help define communities.

Many neurodivergent people have difficulty engaging in social situations and group projects due to sensory challenges. Access to this aspect of civic engagement is important for advocacy.

Civil rights advocacy and community engagement can be achieved by identifying and addressing social and sensory barriers.

I had been invited to speak at a conference at Oxford University in 2017. At that point, Tucker and I had been putting round-the-year effort into a once-a-year event I had founded in 2011, with Tuck coming aboard in 2013. This was a very successful yearly event, and gave me, as its founder, a powerful access pass for many creative opportunities (like speaking at conferences at Oxford).

But the yearly event I had founded was giving lower and lower returns to us personally, although it grew physically every year. The bigger it got, the more aware Tucker and I were that this event was literally and figuratively inaccessible to many. By 2018, we had very good ethical cause to break with it entirely. I founded it, and I had attended and put endless hours of labor into it for years. But when we were “revelling” in this “community” event, I was often scanning the festival site for any Black face other than my daughter’s.

Soon we had ableist and classist concerns as well. Plenty to go into at another time. It’ll be a doozy.

The response we had received at Oxford had been enormously positive. Conference attendees and other presenters seemed to take more seriously the issues of classism, ableism, and racism that lay in the shadows of “community” events where “everyone” was welcome. Those responses helped clarify for us where our notions of success lay, and Tuck’s concept maps felt like the key to how we wanted to refocus.

In 2018, we applied for a grant from the Philadelphia Autism Project. At that time, we were very focused on parade and festal arts for a project we called Civil Rights for Civil Rites, and we had been gathering data from neurodivergent creators. We received funding in both 2019 and 2020, and became friends and colleagues with Zack Inkeles (refer again to the podcast recording with ArtReach, above).

I found, through Instagram, calls to participate in the then-nascent East Kensington WEIRDO Festival. We didn’t know what we’d do there, but we’d take the space, sure. We were given generous free reign to do anything and everything we could come up with at WEIRDO.

Sadly, I was having to reschedule, cancel, or leave Tucker holding the bag with running workshops, or other events. New injuries from my increasingly poor gait issues due to Chiari malformation were frustrating, and made me feel like I was letting people down, and that my own personal disabilities contributed to community failure. I had already identified, publicly, as a speaker, numerous times, that “just” “being present” was often too much for many. Now I felt, in my own body, that it was not just too much; it was also not enough.

Since we had never had a goal of (and in fact, had grown a distaste for) being “in charge” of anything, or identifying ourselves as “helpers” to people who “needed help”, simply gaining a new creative friendship with Zach was more than enough for us. Our approach was naturally person-centered, and therefore we could not only meet Zach where he was, we were open with him about our own limitations. Some of these were things he and Tucker could share, related to not-uncommon autistic issues like sensory overstimulation. Some issues, all three of us (and all neurodivergent) experienced (like pretty low social batteries).

My Chiari symptoms were a multiplier for my sensory issues. And the number of times we had to cancel meetups with Zach — which were as social as they were “work” related — made me feel terrible about myself.

By the winter of 2019, Zach had written an entire script for a puppet production, had found an instrumentalist who had agreed enthusiastically to provide live accompaniment for performances, and we were studying up on rod puppetry, gathering materials, and fleshing out more of Zach’s fairy tale (which, to this day, deserves to be produced and seen.) If we had, that winter, had time to find one more person who felt comfortable learning to use the puppets Zach was making, he would have produced an early version of an orignal puppet show based on the intelligence and lived experience of its author, and a unique view of disability culture. And it could have been produced with entirely autistic talent.

We had not been able to finish things up to be ready for the Winter WEIRDO Festival. We were enthusiastically welcomed to participate in the Spring festival.

And then we went into Covid lockdown.

In 2021, by which point I was officially declared a “permanently disabled” person (still am!), I was asked by Philadelphia Autism Project to be on the organization’s consultant committee, to which I agreed. I thought it was an offer of value —or, that it meant that some of me, which could still be harvested, was worth something to a larger community.

“Now we can’t get the money anymore,” Tucker pointed out. Oh. Right. Because now I was helping to vet other projects that were applying for the money. I had created a conflict of interests with an organization that, sadly, seemed to have little interest in the work we had done. No one from Philly Autism Project had ever attended the workshops we held, including a well-attended shadow puppet workshop that Zach himself had taught. No one from Philly Autism Project, no matter how many times I invited them, had even followed the Facebook pages for Folkfuturism or Civil Rights for Civil Rites.

I did not like being a committee person. It wasn’t hard to keep my mouth shut and not stir the shit during Zoom meetings, because I kept my camera off anyway and didn’t even have to put on a happy face. It was complete bullshit, and is one more thing that will be worth writing about at another time.

There were no festivals or parades in Philadelphia during lockdown. Well, there was Tucker’s “Social Distance Green Man” May Day procession.

Lockdown. Fuck. I had my health issues. The kids needed extra nurturing, as well as new ways to find social contact. (I’ll still fondly remember all their online groups, like Claudia’s Latin class, where she was the only American kid amongst many English children. And the various open-mike or online talent shows she and Béla participated in, solidifying the Talking Heads’ “Thank You For Sending Me An Angel”, with ukulele and cajon accompaniment, as their official party piece.)

Tucker was working towards his Doctorate degree. We were not in a position to be particularly craft-oriented, although, homeschooling continued to avail us of some of the most organic learning and creative moments of our lives as a family.

But to work formally as a “collective” that could offer anything else to anybody else? Or to even have anything to share? Seemed both presumptive and far too ambitious. Staying healthy. Staying afloat. Staying together. That’s what we were doing.

That’s kinda still what we are doing. it’s 2025. In this calendar year, we expect Tucker will become Dr. Collins. In 2026, Claudia graduates high school. in 2027, Béla does.

I’m the catcher in the rye. I’ve also got my own goals, of being able to walk to the Acme and back to shop for dinner, and to make sure it’s cooked and ready when Tucker gets home. And I’d like to be able to do all the dishes without pain or balance issues. I would like, for the next few years, be able to give primary care and nurturing to my family. It doesn’t sound like a lot, going to Acme every day for fresh food and to check out sales (Tucker, a coupon master, went shopping last week and came home with a full cart, and had spent Two. Dollars.)

With the last few years we’ve had, giving Tuck back some of these hours would be truly transformative. I want to savor the last days of my childrens’ actual childhoods. I love that they love me. I love that their friends love me. I’ve already started making the high school graduation afghans that each of the kids’ closest friends will receive as gifts.

Tucker’s concept maps had been generated for specific concepts; for working towards greater inclusion of neurodivergent people into street processionals (either of a cultural nature or of a political nature). There is specificity in the challenge.

What do terms like inclusion, participation, and access really mean? There are probably many answers, but I am very interested in hearing other people’s takes on this.

Is the person “included” just because you can see them there?

Where do you go beyond using video as the single answer to “inclusion”? It’s usually possible to output event footage, live or prerecorded, to an audience. I am not trying to devalue that option, as I was able to be bedridden in Philadelphia and see a close friend’s production in New York via Livestream last month, and it meant a WHOLE lot more than not seeing it at all. As to participation, people can get assistance in inputting — dancing, voices, the costumes of a person who has been able to make their best quality effort on their own timetable, in their own space, whether live or prerecorded. But that can’t be IT… can it? (No.)

I like being part of an art “collective” that consists of projects that just myself and my partner work on, and that also has rotating members, or permanent members who pop up when they have an idea and want to work with us. We will always consider Zach part of our hivemind. There’s no need for all of us to agree on projects that all have equal meaning to us, but we need to care about each other’s projects. We need similar dedication to supporting one another, with our different skill sets, and group decision-making about where and how to look for skill building opportunities. (And, if we are applying for funding, to share that funding with any rotating members.)

What’s behind my own belief that I have any way to offer assistance? Why would I be anyone that people should seek out? I don’t feel like I have better answers or new answers, but I do care. I care a lot, it’s all I’ve got, I wouldn’t let my people rot…

Here are things that I think about.

How do we honor, promote, and model access and inclusion other than to say “Doing it your way is good enough, go for it, yay!” Mick Jagger can yell at an enormous arena audience to clap their hands. Is that inclusion? Is that access? Is it anything? (I’m not picking on Mick Jagger and if anything think he would do a way better job than I’m suggesting by using him as an example.)

What are the differences between access and inclusion?

It’s a nice idea to say “We encourage anyone to participate in any way they can!”, but I’d rather say “We will help you figure out how to make it work. Start to tell us what ‘making it work’ might look like for you.”

And then, stop acting like I was in a position to lead anything. Because in our household, for the next two to three years, believe me, we will need more help than we can give. Ideas, I’ve got. Enormous piles of unfinished projects, notebooks full of unstarted projects… but, (right now), I don’t want to ever “take charge” of anything again. I would be happy to spend my golden years (which have not yet begun) hopping around the UK and offering to do the least glamorous volunteer positions available, and to just watch. (Although my drive to learn giant puppet mechanics is still very strong and is linked, I believe, to my inability to control some of my own body’s movement due to Chiari. Collectively controlling the movement of a large puppet, with others, sounds very soothing and healing, and I will continue to pursue those opportunities.)

One simple, spontaneous inquiry a few months ago, into a folk performance opportunity in the UK, is what inspired this entire post. I told Tucker about it and it made me want to start taking stock of our history. It inspired me to ask questions that I hope will lead to greater inclusion for others, and for myself.

I had seen a call for neurodivergent participants in a folk performance, in England. Since we have done so many things remotely, and encouraged others to participate remotely, I assumed that there was something I could do to participate.

I was told that I lived too far away, live presence was required, and any part of the project that could be done remotely was already being done by others.

I have no entitlement to any project on the planet that is “for” neurodivergent people simply because I am neurodivergent. But, as Tuck’s earliest concept maps show, it’s not air miles that determine whether or not an autistic or otherwise ND person will be able to participate in activity. That, to us, has been the most exciting challenge to our creativity and sense of community all along. If failure to provide physical presence is the biggest barrier to participation, a person a continent away is going to be just as unavailable as an autistic person who has been going to rehearsals all along, and has absolutely no spoons on the day of a performance, and cannot leave the house. In that sense, we are equals.

One thing that can be agreed upon be that if anyone at all says “I would love to be part of this,” the ONLY answer, in this radical community experiment, is “Do you have any ideas about how you can be part of it? What is it you want to share?”

The second thing that can and should be agreed upon is to highlight those points of participation. “Go ahead and do whatever you can do!” is lip service. A parade or a public display of any kind is to put it in people’s faces. Put ALL off it in people’s faces.

What is it YOU want to share? What is the banner you would hold in a parade? What is the mask that would show the real you, inside?